Minnehaha Wins Golden Globe with New Rig and Chainplates

Kirsten Neuschäfer, winner of the Golden Globe Race, adopted a conservative approach to keeping her mast in place for the solo race alone around the world. Langan Design Partners were pleased to help out.

Last spring, a Cape George 36 named Minnehaha sailed into Les Sables d’Olonne, France, on a mere whisper of wind to finish the Golden Globe Race in first place. The circuit lasted 233 days, 18 hours, 3 minutes, and 47 seconds, and at the helm of Minnehaha throughout the grueling singlehanded event was skipper Kirsten Neuschafer, of South Africa.

This is only the third running of the Golden Globe Race, and Kirsten, the first woman to win any around-the-world race via the three great capes, joins a select group. The original event was held in 1968 and won by Robin Knox-Johnston, of the U.K.; the second, held 50 years later, was won by Jean-Luc Van den Heede, of France.

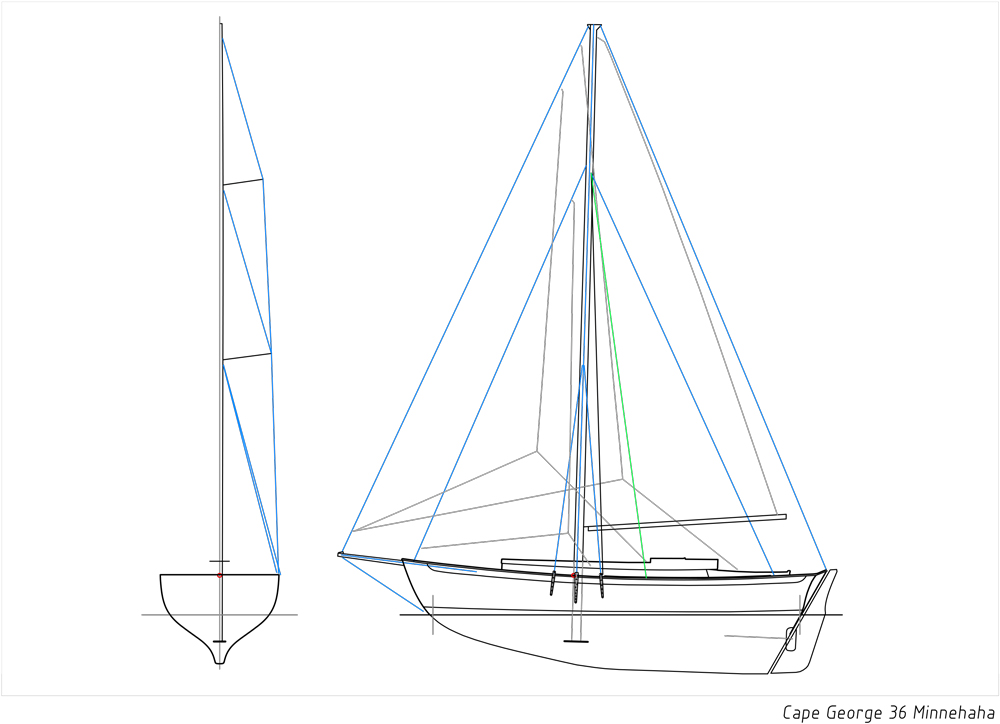

From the sidelines in our offices at Langan Design Partners, we followed Kirsten’s progress throughout and cheered on her extraordinary achievement—she was one of only three skippers among 31 starters to make it around the world without stopping. To make the modern version of the race as challenging as the first one, all boats must be production series boats designed before 1988 and sailed with technology available at the time of the original race. Kirsten’s Cape George 36 was a cutter designed in 1979 by William Atkin and Ed Monk.

At Langan Design Partners, we took quiet pride in what didn’t happen during the race. Before the race, we were asked to assist in selecting a new mast to replace the wooden mast in Minnehaha, but not with a modern one—it had to be an old-style aluminum rig. In addition, Kirsten asked us to design heavy-duty chainplates to anchor the rigging securely.

Naturally, we were thrilled that our work held up throughout the race; as Kirsten noted matter-of-factly afterwards, “On a whole, I am extremely happy with what I had—and the proof lies in the fact that it all survived and performed.”

One of the secrets to Kirsten’s success was her conservative approach. In previous editions of the race, multiple boats pitchpoled and/or lost rigs, and she didn’t want to worry about it.

According to Langan Design’s Tom Degremont, “For the mast, we did a survey of all mast manufacturers to determine what was available and who could supply a mast that would be of an appropriate vintage. From a naval architecture perspective, we got a little information from the company that now handles production of the occasional order for a Cape George 36. We then reached out to mast manufacturers.

Each had a different method of calculating righting moment for the boat and among those, we came up with 15 possible sections.

“The question was how conservative or aggressive we wanted to go in terms of weight. Whether it was for the chainplates or the mast itself, whenever we presented options to Kirsten, she always veered towards the safest, heaviest option rather than a lighter one that might have been faster.

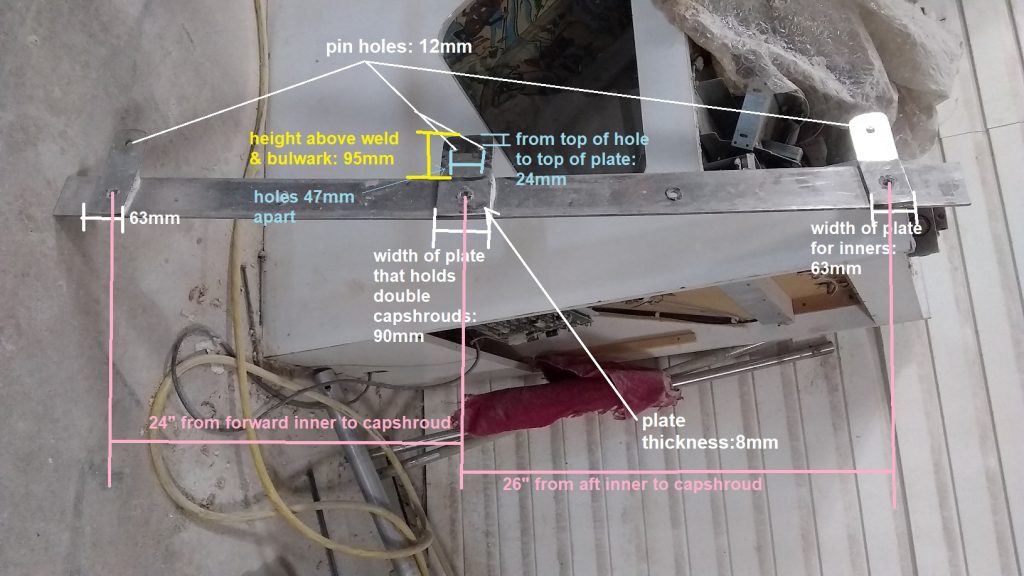

“The mast section Kirsten settled on was by US Spars. The company was very responsive and delivered a strong mast that stood up to the test of the race. “Next, we engineered new chainplates, which had to be stronger not only than the old deck-anchored chainplates, but ready for the loads delivered by the new mast. Stepping a heavier mast also requires specifying thicker rigging, and again Kirsten chose the thicker of every option we gave her.

“As the drawings show, we proposed a tried-and-true approach to the chainplates, making them much longer, so all shroud loads were tied into the hull rather than attaching them to one horizontal bar tied to the bulwark.”

The chainplates designed by Langan Design Partners were fabricated by Eddie Arsenault on Prince Edward Island, Canada, where Kirsten was holed up doing her refit during Covid lockdown.

Eddie worked closely with Kirsten on the myriad of decisions that went into the refit, including the rig: They decided, for example, to ask US Spars to provide compression tubes in the mast so they could go with tangs, like on the original rig, rather than the more modern stem-ball fittings. Eddie also re-built the gooseneck fitting to add strength—a conservative approach that may come from living on Prince Edward

Island! In Kirsten’s words: “I feel Eddie was so instrumental in the whole refit—we made all decisions jointly, and I relied heavily on his opinion.”

Other key players were Jim Teeters, who handled the VPP work, and Alan Burland, who brought us into the project early on.

Our congratulations again to Kirsten, and we wish her the best of luck in her future pursuits.